From guesswork to standards:

The history of medicine quality

In the early 1800s, when people needed medicine, they went to their local apothecary, where the druggist would mix together a medical preparation derived from hand-collected plants and minerals. It might have seemed a bit like watching a barista at a coffee shop mixing ingredients in our favorite morning beverage.

But the potential consequences of inconsistent or poor-quality medicinal ingredients, or a mistake by the person behind the counter could be far more serious than a less-than-delicious cup of coffee. Two hundred years ago, the types and quantities of the drug ingredients varied widely. Patients were sometimes given too little or too much. There were often multiple names for the same medicine. And medicines with the same name didn't always share the same properties. Often "miracle cures" were peddled during traveling side shows.

Medical professionals did their best, but, in some instances, the treatment could be more dangerous than the ailment.

In the years following the American Revolution, as poverty increased and America's water and air became more polluted, people grew sicker. Mainstream medicine became increasingly ineffective.

Americans began to seek out nonconventional medicine and people who embraced these methods, such as midwives, folk healers, and Native American shamans. Tensions grew between trained doctors and the American public looking for more effective cures1.

This growing distrust of traditional medicine was one factor that drove one of the most groundbreaking periods for medical inventions in the 19th century, along with the development of modern medicine in general.

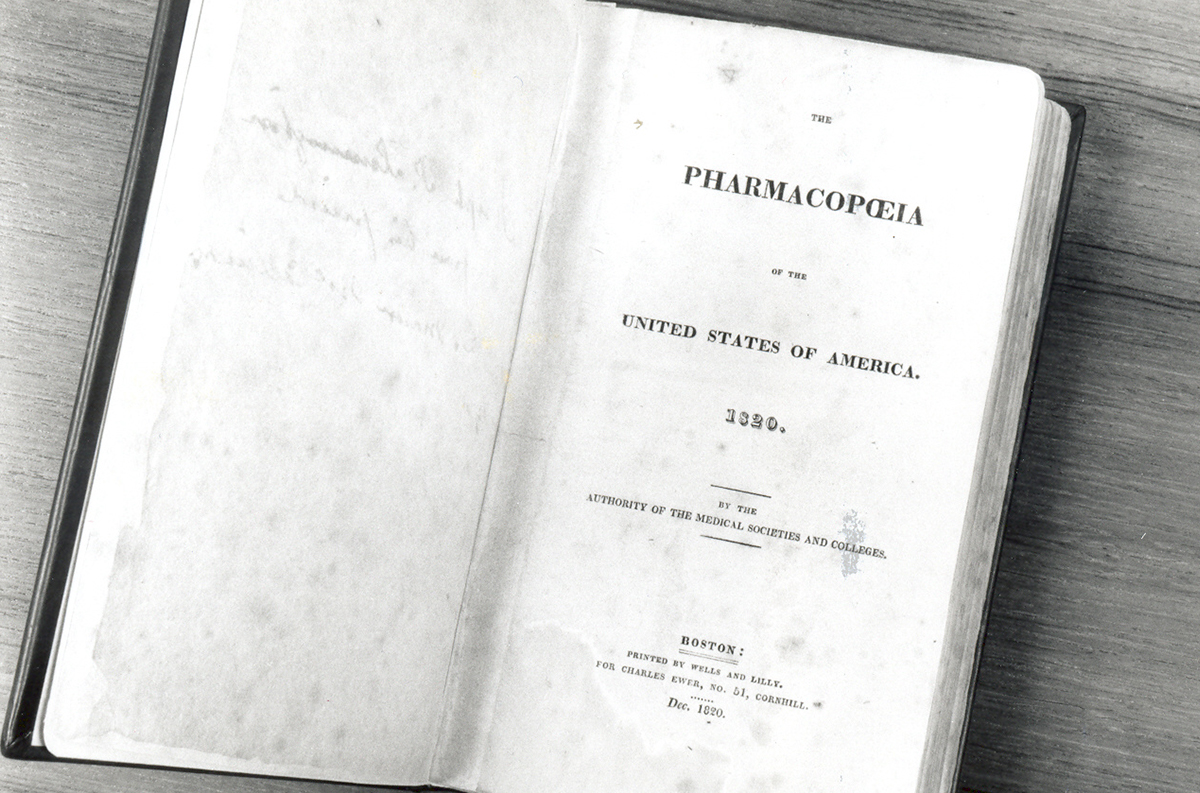

Rising from this tension, Lyman Spalding, a physician and professor from New York, became alarmed when he observed inconsistent and poor-quality medicines threatening the health of his patients. He, with the help of Samuel Mitchill, an American physician, naturalist and politician from New York, convinced other physicians to meet in January 1820 at the United States Capitol to form the United States Pharmacopeia. They put in place standards for the quality of medicines that would protect the public's health. Reflecting the spirit of the young nation, the group would not be part of the government, but instead would remain an independent organization that relied on the latest science to build trust in medicines. The group would meet to continuously revise the science-based standards, which were made publicly available—an early example of using "crowd sourcing" to create an "open source" product for public benefit.

They created a well-defined and clearly described roster of the best understood medicinal substances and preparations of the day that could be used by physicians, midwives and other medical professionals across the newly established United States of America to prepare medicines consistently and to establish independence from Britain. This first edition of the U.S. Pharmacopeia was written in both English and Latin, making it broadly accessible, and was printed at a low cost to make it easily affordable.

From a resource to an authority on medicine quality

USP evolved from a resource into an authority, as the federal government began asserting itself as an overseer of drug quality. The U.S. Pharmacopeia was first officially recognized with the Drug Importation Act of 1848, enacted to stop the importation of poor-quality medicines by drug makers in Europe, who stamped the products "good enough for America." This legislation armed U.S. customs inspectors at ports of entry with tools to identify drugs that were substandard or adulterated.

Responding to tragedy

The role of government regulation of medicines continued to grow in the early 20th century. Sadly, this often occurred in response to a tragedy resulting from the use of poor-quality medicines.

Beginning in the late 19th century, an injection of antitoxin saved the lives of countless diphtheria patients, most of them children. But in 1901, the treatment turned deadly when 13 children were injected with diphtheria antitoxin contaminated with tetanus. One physician who had administered the diphtheria antitoxin lamented, "There I found that the little girl was suffering from tetanus (lockjaw). I could do nothing for her. The poison was injected so thoroughly into her system that she was beyond medical aid."

Physicians and patients trusted the antitoxin, but its purity hadn't been verified. A horse whose blood was used to produce diphtheria antitoxin had died of tetanus. The contamination could have been discovered, but the serum hadn't been tested. The antitoxin produced from the contaminated serum was distributed and sold, resulting in the deaths of all 13 children.

This tragedy, and a similar incident involving smallpox vaccines, led to multiple laws designed to monitor and regulate the quality of medicines. One such act in 1906 officially recognized USP standards for strength, purity and quality of medicines.

But recognition in federal legislation is not the same as companies being required to use USP standards. That changed in 1938 with the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which was enacted in response to another tragedy caused by unsafe medicine. The new elixir sulfanilamide was tested for appearance and taste but not for safety before it was introduced into the market. More than 100 people died as a result.

Patients trust physicians. Physicians trust the medicines they prescribe. But there needed to be a way to make sure that the medicines were worthy of that trust. In response to public outcry, Congress declared in the 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act that all medicines sold in the U.S. must meet applicable USP quality standards. USP remained an independent, nonprofit organization that was (and is) not part of the U.S. government.

Building trust in generic medicines

As healthcare evolved over the years, USP adapted to the changes, including pivotal U.S. legislation in 1984 that increased people's access to generic drugs.

Before a new drug is brought to market, the manufacturer must prove that it is safe and effective. With passage of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, known informally as the Hatch-Waxman Act, manufacturers of generic versions of a branded drug are no longer required to submit clinical data demonstrating safety and efficacy. They are, however, required to show that the generic meets the same standards for identity, strength, purity and quality, and is therapeutically equivalent to the branded product.

USP standards help companies develop generic medicines by providing manufacturers with specifications, testing methods and other requirements, as well as guidance on expectations for quality. By enabling generic drug manufacturers to demonstrate equivalence and bring their products to market, USP standards help give healthcare professionals and patients access to more treatment options along with confidence in the quality of generic drugs that they're prescribing and taking.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Today's medicines and therapeutic technologies were unimaginable when USP was founded 200 years ago. Drugs have evolved from plant- and mineral-based to synthetic chemicals and small molecules to recombinant biologics and beyond. The world has gotten smaller. Diseases travel. Drug resistance grows. Poor-quality medicines kill. More countries are now part of the global supply chain for pharmaceuticals. This interconnectedness, along with a shift from infectious to more chronic diseases, has brought about new public health and medicine quality issues that affect everyone.

But the need hasn't changed: Whether it's to treat an injury, illness or chronic health condition, people must be able to trust medicines. And that need is universal.

Beginning with the first translation of the USP into Spanish in 1908, USP's mission to improve public health through its standards has extended beyond U.S. borders. Whether protecting the integrity of the global pharmaceutical supply chain, strengthening quality assurance across health systems or helping to curb antimicrobial resistance, USP is working to protect the health of all people, no matter where they live.

Restoring trust in the wake of poor-quality medicines

Around the world, tens of thousands of deaths occur each year because of substandard and falsified medical products. Most affected are low- and middle-income countries that lack resources and infrastructure to ensure adequate oversight. Knowing that medicines may not work the way they're supposed to has led to a lack of trust in health systems and people forgoing potentially lifesaving treatments.

USP works with regulators, manufacturers, healthcare providers and consumers to build trust in the quality of medicines around the world. Partnering with national regulatory authorities and international agencies, USP has helped resource-limited countries build their regulatory systems' ability to oversee and manage drug quality. USP's international offices and state-of-the-art labs offer training programs so local manufacturers use quality standards effectively. By supporting the manufacture of quality-assured medicines for diseases like malaria, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, USP has helped make inroads into restoring communities' trust in healthcare and medicine, so more people can get the treatments they need to live longer and healthier.

Responding to global public health threats

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when bacteria and other microbes adapt and become less susceptible to medical treatment. Resistance is often attributed to the improper use of antimicrobial medicines, but there is increasing evidence that medicine quality is another contributing factor. Medicines with a lower dose of the active ingredient can lead to resistance.

USP's international network is critical in helping to address global public health threats, including the spread of AMR. Beyond the proper use of standards to confirm drug identity, purity, strength and quality, USP is working with local regulatory agencies and healthcare service providers to better detect substandard drug products and improve access to quality antimicrobial medicines. USP is also committed to raising awareness of the connection between medicine quality and AMR so policymakers can make informed policy decisions and fostering partnerships to advocate for strong regulatory and quality assurance systems.

Protecting the global supply chain

Today, more than 80% of medicines or medicine ingredients come from outside of the U.S. These drug products and ingredients travel from suppliers to manufacturing sites to wholesalers and warehouses, to distributors, to pharmacies, and ultimately to patients. The more complex the supply chain, the greater the risk that the quality of the medicine may be compromised somewhere and pose a risk to patients. USP standards provide a common quality benchmark—a set of characteristics, processes and guidelines that apply to all medicines and their ingredients, regardless of where they are manufactured. USP standards and best practices for handling and storage requirements help ensure the quality of medicines for patients all over the world. When manufacturers across the supply chain comply with USP standards, they help ensure medicines' consistency and quality. So, no matter where you live, you can trust the quality of your medicine.

Protecting the integrity of the global supply chain, strengthening quality assurance across health systems and responding to global health threats like antimicrobial resistance are a few of the ways that USP standards and programs are building on the foundation laid by a handful of physicians 200 years ago. Did they recognize the impact their actions would have or the legacy they would leave? It's doubtful. They saw a public healthcare need and they acted to remedy it. The integrity and initiative of its founders will forever remain a cornerstone of USP and a fundamental reason why regulators, manufacturers, healthcare professionals and patients around the world can trust products that meet USP quality standards.